A simple dice game — with a harrowing climate message

In this edition: Space law, a catchy song about eels mating, and a media landscape licking its wounds.

Hello! Welcome to Deviations, and thank you so much for signing up.

If you have any feedback or suggestions, please send comments my way via this contact form. And if somebody forwarded you this newsletter and thought (correctly) that you’d like it, sign up to receive future editions.

What I’ve been up to

My son’s first walking Halloween. He was a cow, he was very cute, and he became fast friends with “Boo,” an inflatable ghost decoration on our front porch. I dressed as what one trick-or-treater at my house called “Halloween Guy”: a generically spooky groundskeeper type with an electric-candle lantern.

An unexpected honor. The October 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine featured my last story as a staff writer there: an in-depth look at Artemis, NASA’s ambitious moon program. To my delight, I recently learned that the story was named a “notable” piece of writing in this year’s edition of the Best American Science and Nature Writing anthology. Check out the feature here.

Law! In space! I wrote the cover story for the fall issue of Texas Law Magazine, a new alumni magazine for the UT Austin School of Law, all about the new legal questions raised by the rapidly growing commercial space industry. Many thanks to my sources; to photographer Dan Winters, who contributed images to this story (and photographed my National Geographic Artemis feature); and to Liz Hilton, the talented editor who leads Texas Law Magazine and commissioned me.

Things you should check out

A Capella Science. Tim Blais’s long-running YouTube channel is a blast. Since 2012, Blais has been rewriting pop songs to be about something science-y — gene editing or dinosaur evolution, for example — and then recording elaborate arrangements of them. His latest creation, an ode to eel mating through the music of Sabrina Carpenter, is worth a listen:

Matt Pearce’s Substack. I recommended some of his work last time, but in the election’s aftermath, the union leader and former Los Angeles Times journalist has been on an all-time heater with commentary on the woeful state of our information economy. In an essay on Monday, he described journalism as being in a “fight for survival in a postliterate democracy.” I’m inclined to agree.

“You Are the Media Now.” Charlie Warzel, a writer for The Atlantic, wrote an excellent (and grim!) piece recently about how fragmented, opaque, and confusing our media landscape has become.

The Southern Reach books. With mere words, author Jeff VanderMeer does to your mind what fungi do to a rotting log: infiltrates and burrows until, eventually, something both gross and beautiful rises from the fuzz. His Southern Reach series focuses on a mysterious agency charged with exploring “Area X,” a coastal region that nature is reclaiming — and where nature behaves in surreal, horrifying ways. The first three books of the series are among my favorite books. The latest, Absolution, just came out; I haven’t read it yet, but I hope to get to it soon.

Bluesky. The social media platform and Twitter/X competitor has gotten much livelier over the past week with the arrival of many journalists, academics, and news junkies. Check it out if you’re into that sort of thing. If you join, follow me!

The Deep Dive: Climate Dice

Over the years, I’ve thought long and hard about ways to illustrate climate change: specifically, how we’re skewing the probabilities of different weather outcomes. Early last year, I came up with one I wanted to share with you.

At any given time, weather is chaotic. Even subtle changes to starting conditions can lead to varied outcomes that are hard to predict in advance. But just as a dog on leash can wander to and fro while her owner walks a deliberate route, our ever-fluctuating weather still obeys larger climatic trends:

By increasing how much heat our atmosphere retains (via greenhouse gases), we’re pushing our planet out of energy balance. Little Boy, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, released roughly 63 terajoules of energy. From 1971 to 2020, Earth gained an extra 381 zettajoules of heat. That’s about 20% more energy than we would have released if we had detonated two Little Boys per second every single second from August 6, 1945, to today.

As it spreads around Earth, this excess heat alters the long-term weather patterns that we humans have come to rely on (for things like, oh, I don’t know, global agriculture and coastal infrastructure). To use another analogy: If the weather at any given time represents a single roll of the dice, climate change is what happens when the dice get loaded. As it turns out, you can take this analogy pretty far.

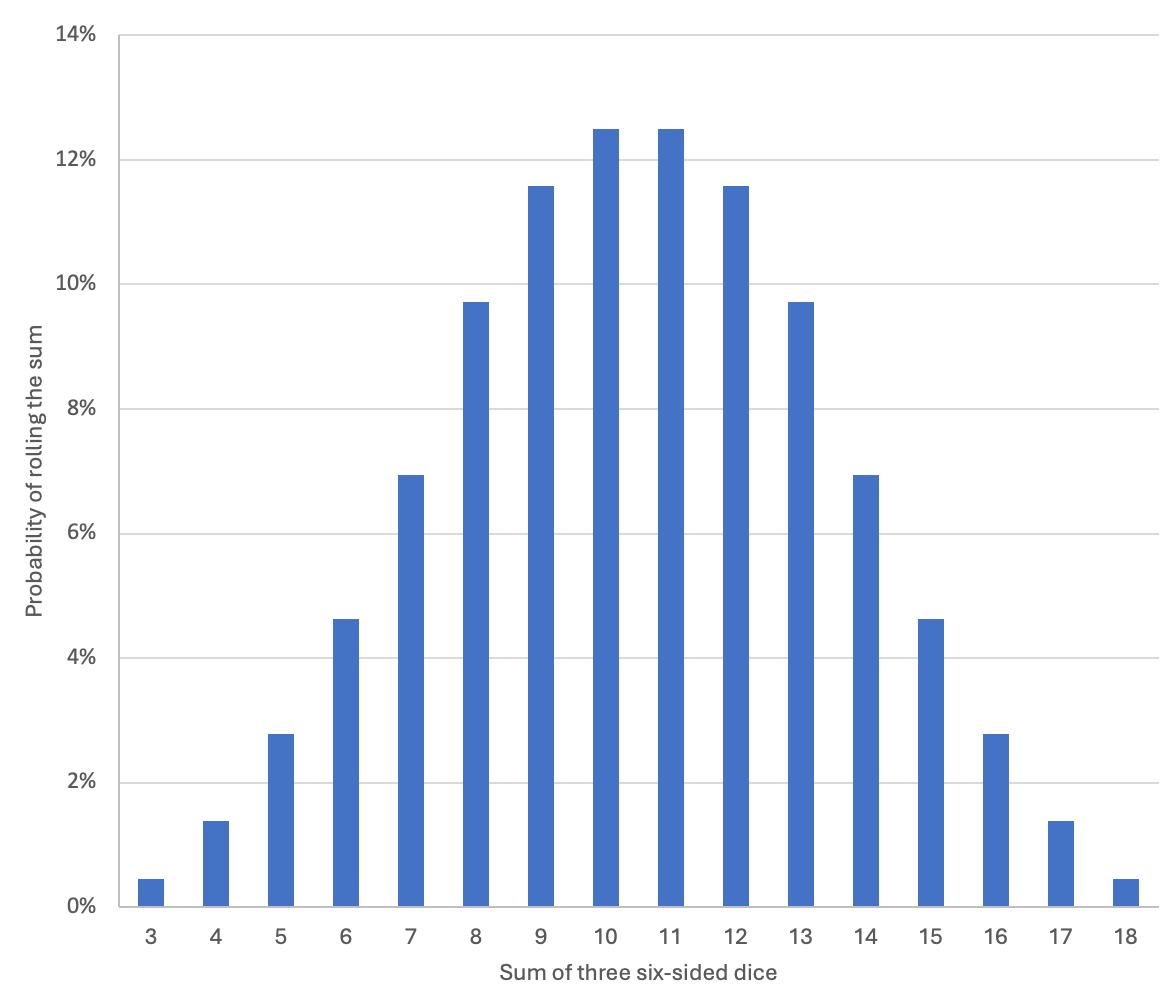

Probabilities in dice

Roll three standard six-sided dice and add up what you get. The possible sums can be any integer from 3 to 18, but your odds of getting any given sum will vary. You have less than a 1-in-200 chance of getting the dice to add up to 3, since each die roll must be exactly 1. However, you have a 25% chance of three dice adding up to either 10 or 11, since there’s so many combinations that can hit those totals (for 10, a 4 and two 3s, a 6 and two 2s, etc.).

Taken all together, these probabilities approximate what’s known as a normal distribution, or what you may have heard called a “bell curve”:

Normal distributions pop up all the time in nature; we see them in the ranges of human heights and summer temperatures, for example. If we think about climate change in terms of normal distributions, what’s basically happening is that all the excess heat we’re adding to Earth is shifting the bell curve of weather.

This move does shift the average (the peak), but the real danger is out at the far end of the curve. Rare, destructive weather extremes become much more frequent when average conditions shift even slightly toward them.

For decades, scientists have thought about using dice as a way of visualizing these shifts in the context of climate change. In a landmark study on climate simulations published in 1988, researchers including NASA scientist James Hansen outlined what may well be the first connection between climate change and dice rolling:

With hot, normal and cold summers defined by 1950-1979 observations [...] the climatological probability of a hot summer could be represented by two faces (say painted red) of a six-faced die. Judging from our model, by the 1990s three or four of the six die faces will be red. It seems to us that this is a sufficient “loading” of the dice that it will be noticeable to the man on the street.

Like Hansen and his colleagues did four decades ago, I’m going to be equating the outcomes of dice rolls with the frequencies of extreme heat. However, I’ll be taking advantage of a coincidence I found that aligns with more up-to-date data and makes it easy to build in varying amounts of global warming.

Welcome to Climate Dice!

Climate Dice in action

Your supplies: three standard, six-sided dice. (Or even one die, if you roll it three times and remember what you rolled! Whatever floats your boat.)

First, let’s define some terms that will be be used a lot below:

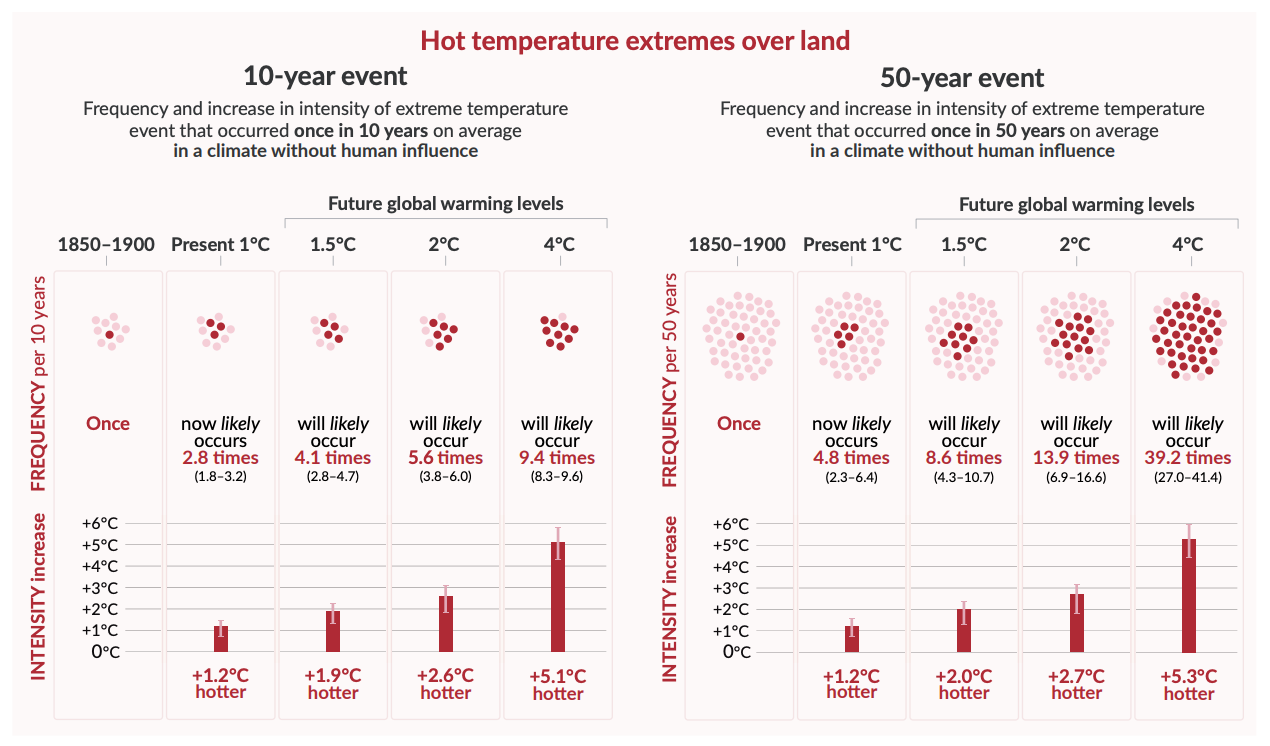

- A “10-year heat event” is what would have been, on average, a once-in-a-decade hot temperature extreme over land during the years 1850-1900. We can think of this, roughly, as a heat extreme that would have had a 10% annual chance of occurring during the back half of the 19th century.

- A “50-year heat event” is what would have been, on average, a once-in-50-years hot temperature extreme over land during the years 1850-1900. Similarly to above, we can think of this as an event with a 2% annual chance of occurring.

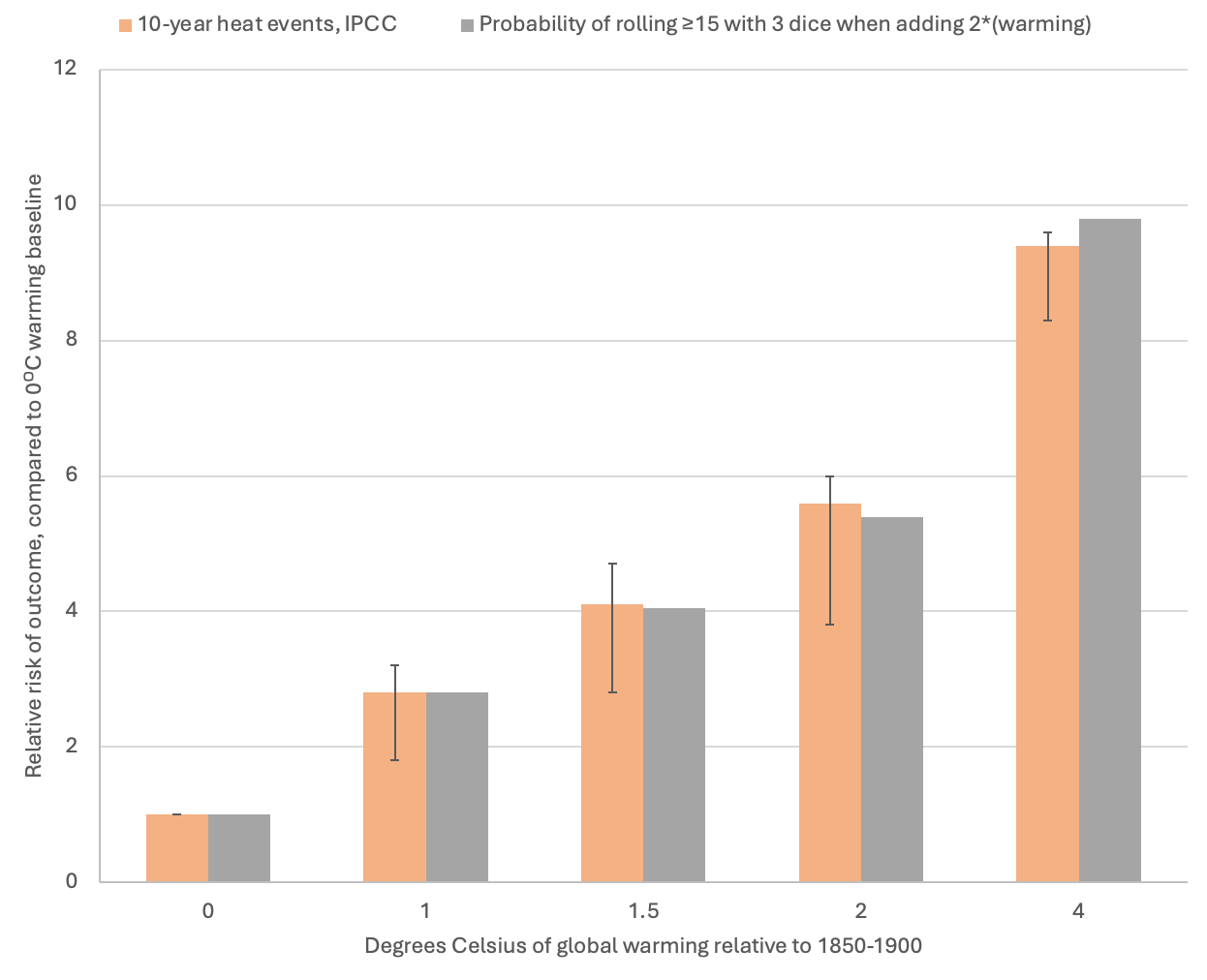

As it happens, those annual percentages align pretty well with the probabilities of certain three-dice rolls. With three standard six-sided dice, you have a 9.3% chance of rolling a sum of 15 or more, and you have a 1.9% chance of rolling at least a 17. We’re going to define rolling a 15 or higher as a 10-year heat event and rolling a 17 or higher as a 50-year heat event.

Under these definitions, there happens to be a surprisingly accurate way to represent climate change. For every 0.5°C of warming since 1850-1900 that we’re simulating, we simply add an extra 1 to our score.

Putting it all together, here are the rules for Climate Dice:

- We roll our three dice;

- We add up what we get;

- We add an extra 1 for every 0.5°C of warming; and

- We check whether our new sum is at least 15 (for 10-year heat events) or at least 17 (for 50-year heat events).

Simply adding an extra 2 is enough to increase the chances of rolling 15 or more by a factor of 2.8, from 9.3% to 25.9%. That increase is identical to what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports has happened to 10-year heat events over the past century.

According to a 2021 IPCC report, we’ve already seen 1°C of global warming relative to 1850–1900. And as you can see on the left side of the chart below, what were once 10-year heat events have already gotten about 2.8 times more common:

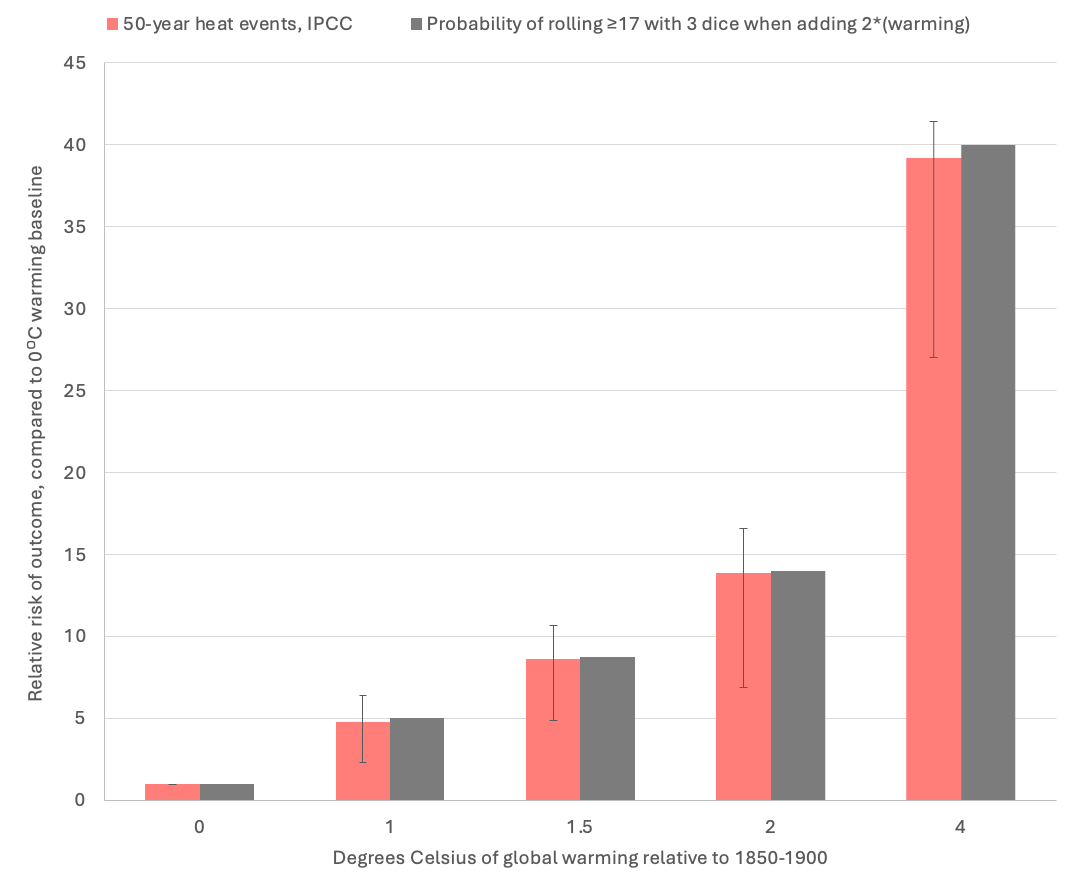

Within Climate Dice, the shifting probabilities of rolling at least a 15 or a 17 jibe remarkably well with IPCC estimates of how much more frequent heat events are expected to get. This coincidence works for both 10-year heat events and 50-year heat events, and it appears to work well through up to 4°C of future warming.

The two charts below show the correspondence. The orange and salmon-colored bars represent how heat events’ probabilities increase under different amounts of warming (relative to the 1850-1900 baseline). The gray-colored bars represent the Climate Dice equivalents as I have defined them:

It’s not perfect, but as far as rolling dice goes, I’d say that’s pretty good.

Running up the score

Let’s stop for a moment and consider what all this dice rolling actually means. In real life, we are very close to locking in 1.5°C of global warming relative to 1850–1900. We are almost certainly going to exceed this threshold, what with the United States (the world’s largest economy and biggest historical emitter of greenhouse gases) now poised to gut many of its climate policies.

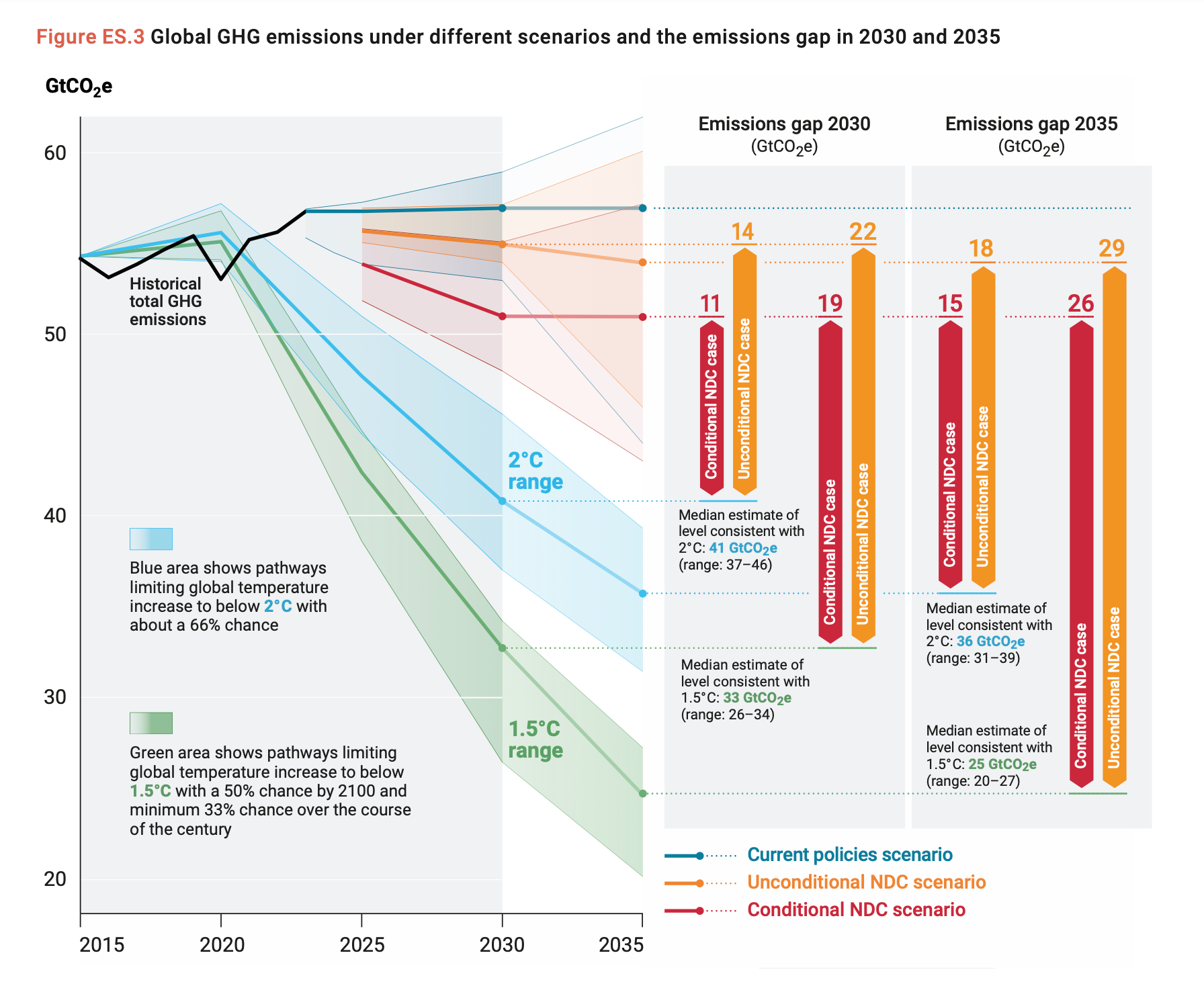

Under the Paris Agreement, the global climate pact negotiated in 2015, nearly all of the world’s countries have committed to aim for just 1.5°C of warming above 19th-century levels and to limit warming to well below 2°C.

However, global commitments to fight climate change have us on track for roughly 2.6–3.1°C of warming. There’s a gigantic gap between the emission cuts that are needed to limit warming to 2°C (the blue area in the chart below) and our current trajectory (the orange or red areas, depending on how generous we want to be):

These may sound like small amounts at first; what’s a few degrees among friends? But remember when we were talking about all those atomic bombs? A staggering amount of heat is needed to raise the average temperature of our entire planet’s surface by a single degree. The resulting effects on extreme weather are huge.

If we’re playing Climate Dice with the near future (1.5°C) in mind, we’re adding an extra 3 to our score, at a minimum. That shift roughly quadruples how often we’ll see 10-year heat events (rolling 15 or more) and more than octuples how often we’ll see 50-year heat events (rolling 17 or more). Gulp.

A full 2°C of warming (adding an extra 4 in Climate Dice) more than quintuples the likelihood of getting a 10-year heat event (rolling 15 or more). The probability of getting a 50-year heat event (rolling 17 or more) goes up by a factor of about 14.

If 2°C of warming comes to pass, the hottest one or two summers my great-great-grandparents ever experienced will happen once every four years or so for my children and grandchildren. And on our current path, 3°C is on the table.

We’re already in for a world of hurt. In a sobering 2018 report, the IPCC announced that in 1.5°C of warming, 70–90% of the world’s coral reefs are expected to die off because of marine heatwaves, dealing a major blow to the many species that depend on reef ecosystems (including us). If we reach 2°C of warming or more, more than 99% of all coral reefs will perish, and the Arctic will become ice-free during the summer at least once per decade.

Climate change is “loading the dice” for many different weather events all over the world, all at once — with consequences we are still racing to understand. As I hope this exercise makes clear: We need to limit this loading as much as possible. Every extra bit of climate forcing makes destructive extremes that much more likely.

For those who want to simulate climate change within a board game or classroom lesson, this may be an interesting exercise to use. Please feel free to adapt Climate Dice however you see fit, but please cite me and let me know if you end up using it.

To close, here’s an anagram summary:

That’s it for this edition of Deviations! Please send along any feedback you may have via this contact form, and once again, consider clicking this button: